The DSM, determined by form

The DSM, determined by form

This blog is part of the series ‘The RFT Glossary‘. RFT stands for Relational Frame Theory. It’s a remarkable theory about the interplay between language and our behaviour. RFT can be somewhat challenging for newcomers to grasp. It includes many terms that almost seem like a foreign language. That’s why these blogs exist – as a sort of glossary for RFT. The bolded words in the text can be found in the glossary.

In the previous blogs, we’ve seen that truth and evidence are contingent upon how you perceive life: your world view. We’ve asserted that you cannot view life without a world view. A general world view is also referred to as a world hypothesis by the philosopher of science, Pepper (1942). Some world hypotheses are conducive to science, while others are not. In the previous blog, we examined the two world hypotheses that are unsuitable for science. This week, we scrutinize the first world hypothesis that is indeed suitable for science: formism.

Formism

In the world hypothesis known as formism, the central idea is that everything we experience consists of various forms. Each form is unique, yet they share similarities and differences with one another. For instance, every tree is unique, but each tree shares certain characteristics with other trees. These shared attributes define a tree (such as a trunk, bark, and leaves or needles). Let’s delve deeper into formism with some examples.

Unique forms and their attributes

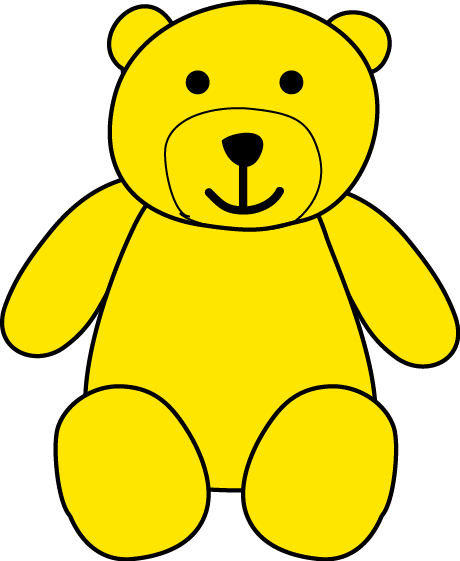

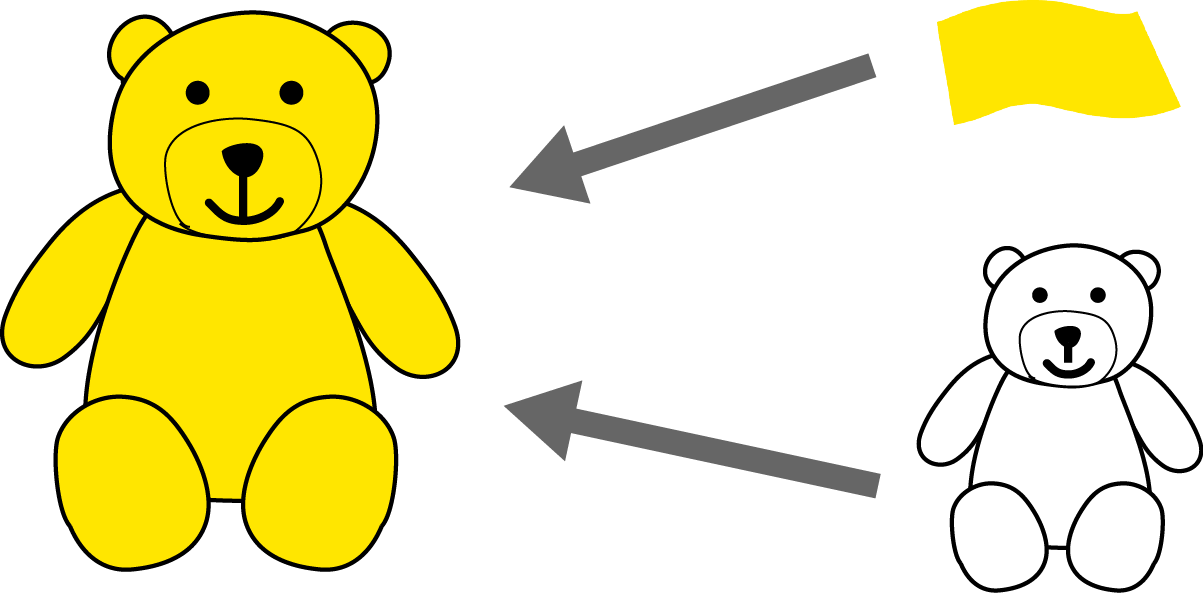

Consider this yellow teddy bear above. This bear can be seen as a unique form. We can state that this unique form possesses the following attributes: ‘resembles a bear’ and ‘yellow’. Schematically, it appears as follows:

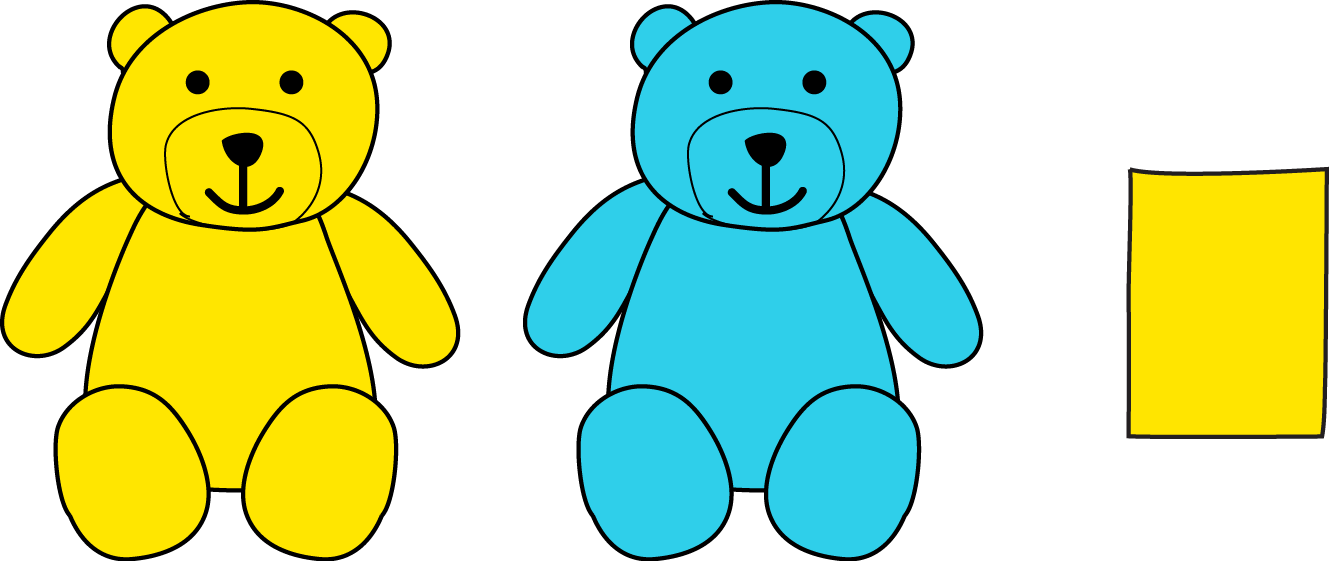

Let’s add a few other unique forms to our unique yellow teddy bear, namely: a blue teddy bear and a yellow sheet of paper. Now we have three unique forms: a yellow teddy bear, a blue teddy bear, and a yellow sheet of paper. The blue teddy bear and the yellow teddy bear share the attribute ‘resembles a bear’. The yellow teddy bear and the yellow sheet of paper share the attribute ‘yellow’.

Categories

We can now create categories. We do this based on the attributes that the unique forms share with each other. For instance, we can form the following categories:

- Resembles a bear

- Yellow

The yellow teddy bear and the blue teddy bear fall under the category ‘resembles a bear’. The yellow teddy bear and the yellow sheet of paper fall under the category ‘yellow’. The category is determined by the shared attributes.

Each category can also have subcategories. For instance, every tree can be divided into a type of tree (e.g., oak tree, maple tree, etc.). Each type of tree shares specific attributes with other trees of its kind. These specific attributes are not found in other types of trees. For example, an oak tree has a certain leaf shape that other types of trees don’t possess. This allows an oak tree to be distinguished from other trees, such as a maple tree.

In summary, attributes are integral to unique forms. You can establish categories based on attributes. Unique forms can be part of a category due to shared attributes inherent to that category. This approach enables us to differentiate between various unique forms.

Truth

As discussed earlier, each world hypothesis has a criterion for truth. In the case of formism, something is deemed true based on correspondence. Something belongs to a specific category when the attributes of the unique forms correspond with those of the category.

Formism in psychology

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the book in which disorders are categorized (APA, 2022), is quintessentially a formistic approach to psychology. Within the DSM, symptoms of behavioural disorders are classified. The DSM emerged from a need for consensus. Prior to the introduction of the DSM, there was a maze of different names for certain behaviours. No one knew precisely what was meant by terms like ‘depression,’ and each individual had their own interpretation. Hence, a need for consensus arose, leading to categorization based on discernible outward symptoms. In this manner, the creation of the DSM was rooted in formism, perhaps even unconsciously.

Specifically, we can observe formism within the DSM in the categorization of behaviour based on attributes, also referred to as symptoms. Furthermore, it’s evident in the notion that these outward symptoms (attributes) convey something valuable about the unique behaviour (unique form). Formism is also apparent in the criterion for truth. According to the DSM, it’s considered true that someone has depression when their behaviour aligns with the outward symptoms (attributes) associated with the ‘depression’ category.

Unlike the DSM, formism isn’t widely prevalent in psychology. It’s relatively limited in its approach, particularly when dealing with more complex processes that influence behaviour.

Next week, we’ll delve into organicism, which takes a cyclical approach.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Pepper, S. C. (1942). World hypotheses: A study in evidence (Vol. 31). Univ of California Press.