Science, evidence, and truth through different lenses

This blog is part of the “RFT Dictionary” series. RFT stands for Relational Frame Theory, an incredible theory that explores the relationship between language and behavior. RFT can be challenging for newcomers to grasp, as it incorporates numerous terms that may seem like a foreign language. That’s why these blogs exist—to serve as a sort of dictionary for RFT. The bolded words in the text can be found in the dictionary, providing definitions and explanations to enhance your understanding.

Science and truth

You may often come across headlines like “Science reveals that…” or “Science proves that…” in news articles. In our society, science is generally seen as a pursuit that can uncover the truth about how our world works and how we function. We believe there is one truth that exists outside of us, waiting to be discovered. Once we know this truth, we are certain. We know what to do, which choices to make, how the world operates, what is real, and what is not.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a popular concept in psychology. EBM refers to therapies for which there is evidence of effectiveness. But when do we consider something as effective? How do we establish evidence? What underlies this evidence? When is something true? To explore these questions, we turn to Pepper (1942), a philosopher of science who studied truth.

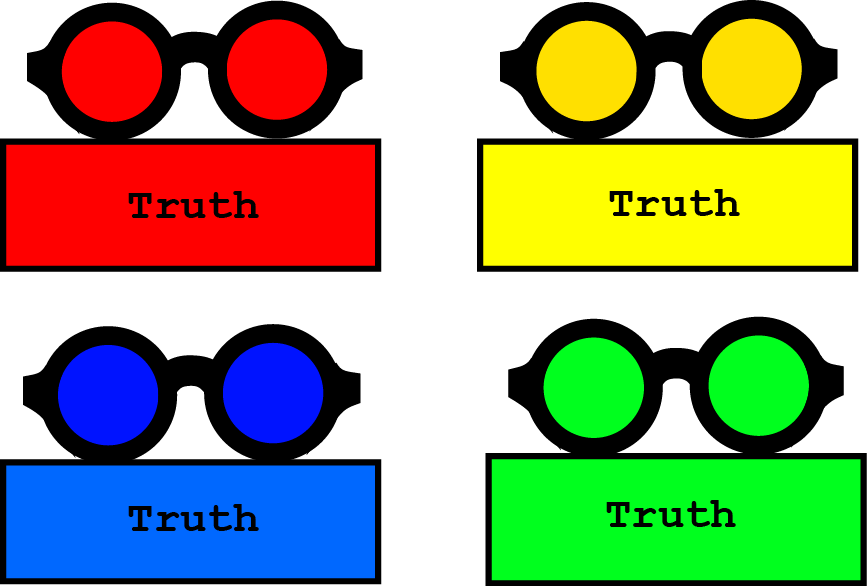

Pepper argued that what is considered evidence and truth depends on your worldview. A worldview is a perspective from which you view life, similar to wearing a pair of glasses. When you put on red-tinted glasses, you see the world as red. When you put on blue-tinted glasses, you see the world as blue.

Can’t I go on without glasses?

Now you might be thinking, “Well, then I won’t wear any glasses, and I’ll see the world as it truly is.” But that’s not possible. You cannot go trough life without a worldview, and this applies to scientists as well. A scientist is not a blank slate when they embark on their research. They don’t hatch from an egg and start asking questions and conducting investigations.

A scientist also grows up and develops within a community that provides them with a set of glasses. Perhaps they may switch glasses later on, but they will never be able to look at the world without glasses. Their glasses determine which research questions are relevant and which are not, how they design their research, which factors they consider important to include, and ultimately, what they consider as true or as evidence for their research question. In future blogs, we will explore how these worldviews also influence how we view therapy, what we expect from therapy, therapists, and research on therapy.

World Hypotheses

Pepper describes six different global worldviews, which he refers to as “world hypotheses.” According to him, they are hypotheses because they cannot be tested. They are pre-analytical assumptions, which means they are assumptions made before conducting any research or analysis. All six world hypotheses will be further discussed in future blogs.

Truth is dependent on your worldview or world hypothesis

According to Pepper, each world hypothesis has its own perspective on truth. Each world hypothesis has its own criterion for determining when something is true, he says. These criteria of each of the world hypotheses are called a “truth criterion.” Therefore, there are multiple truths (truth criteria) that are associated with a worldview or world hypothesis. What we perceive as evidence is also influenced by the world hypothesis we adhere to. We will see how this unfolds when we delve into the specific world hypotheses.

In summary, science can be practiced from different worldviews. Pepper distinguishes six global worldviews, which he refers to as world hypotheses. Each world hypothesis has its own truth or truth criterion. What you consider as evidence is therefore dependent on the lens you wear or the world hypothesis you adhere to.

Some world hypotheses are suitable for science, while others are not. I will explain this in the next blog post.

References

Pepper, S. C. (1942). World hypotheses: A study in evidence (Vol. 31). Univ of California Press.